- Planet Earth

- Volcanos

A 1956 eruption collapsed much of the Bezymianny volcano in Kamchatka, Russia, but frequent eruptions since — including a large event in November — means it has now almost completely regrown.

0 Comments Join the conversationWhen you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

The volcanic eruption of Bezymianny on March 30, 1956. The blast caused the volcano to collapse.

(Image credit: Photo by I. V. Yerov, 1956 (courtesy of G.S. Gorshkov, published in Green and Short, 1971, Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0).)

The volcanic eruption of Bezymianny on March 30, 1956. The blast caused the volcano to collapse.

(Image credit: Photo by I. V. Yerov, 1956 (courtesy of G.S. Gorshkov, published in Green and Short, 1971, Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0).)

A restless Russian volcano sent an ash cloud 32,800 ft feet (10 kilometers) into the air in late November in an eruption that may bring the mountain closer to its original height.

The Bezymianny volcano is a dramatic, cone-shaped stratovolcano on the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Russian Far East. It blew itself apart in 1956, but a 2020 study found that it has nearly grown back — and eruptions like the one that created an ash plume on Nov. 26 are the reason. That study found that the mountain should achieve its pre-collapse height between the years 2030 and 2035.

You may like-

Scientists discover new way to predict next Mount Etna eruption

Scientists discover new way to predict next Mount Etna eruption

-

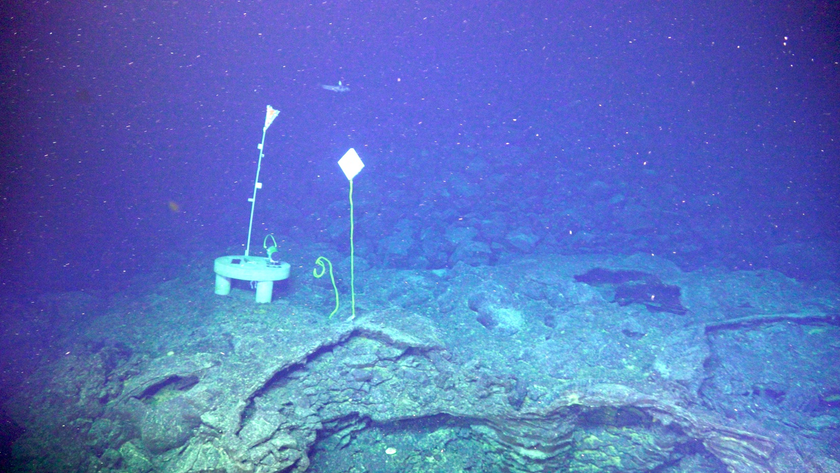

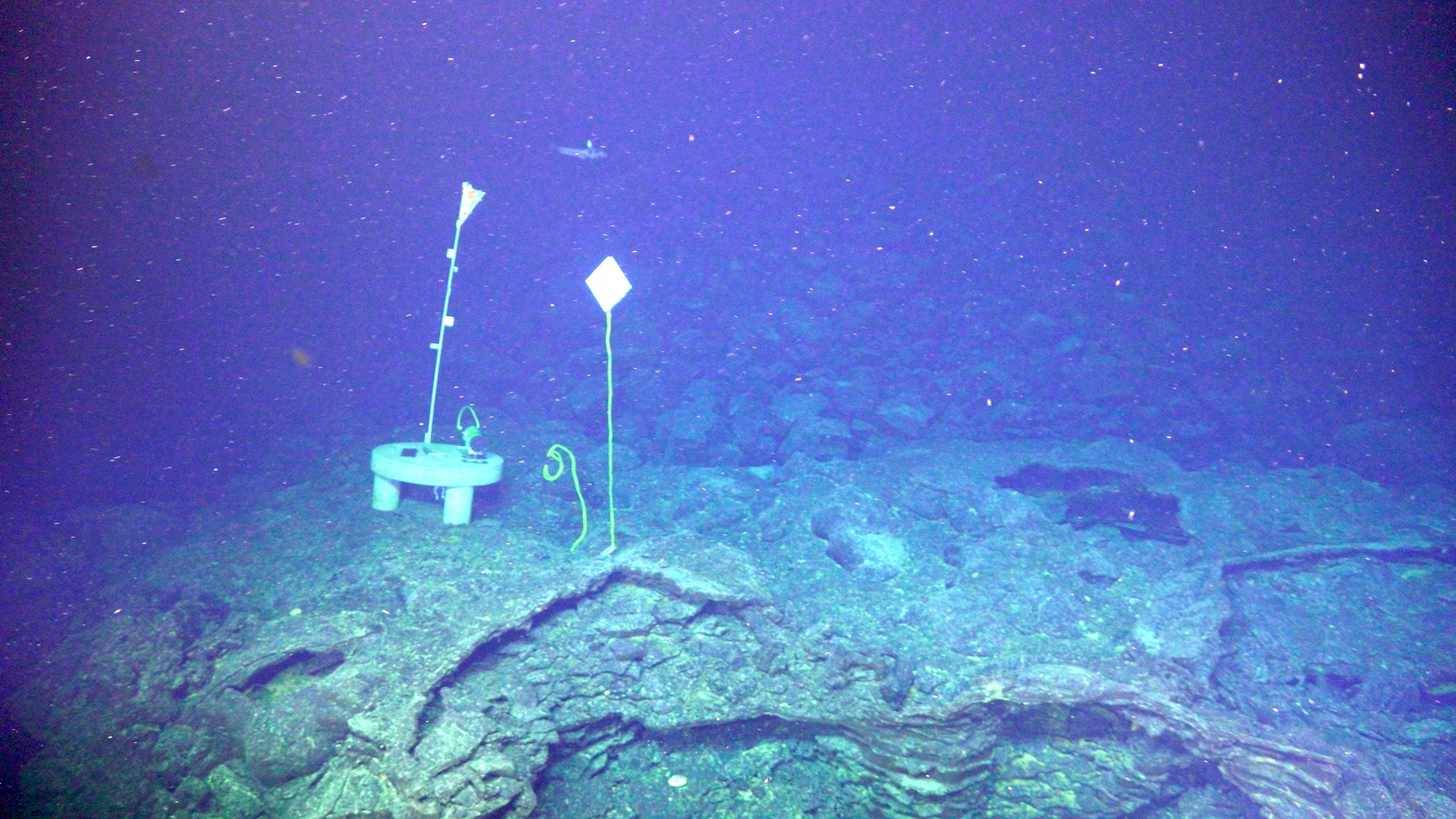

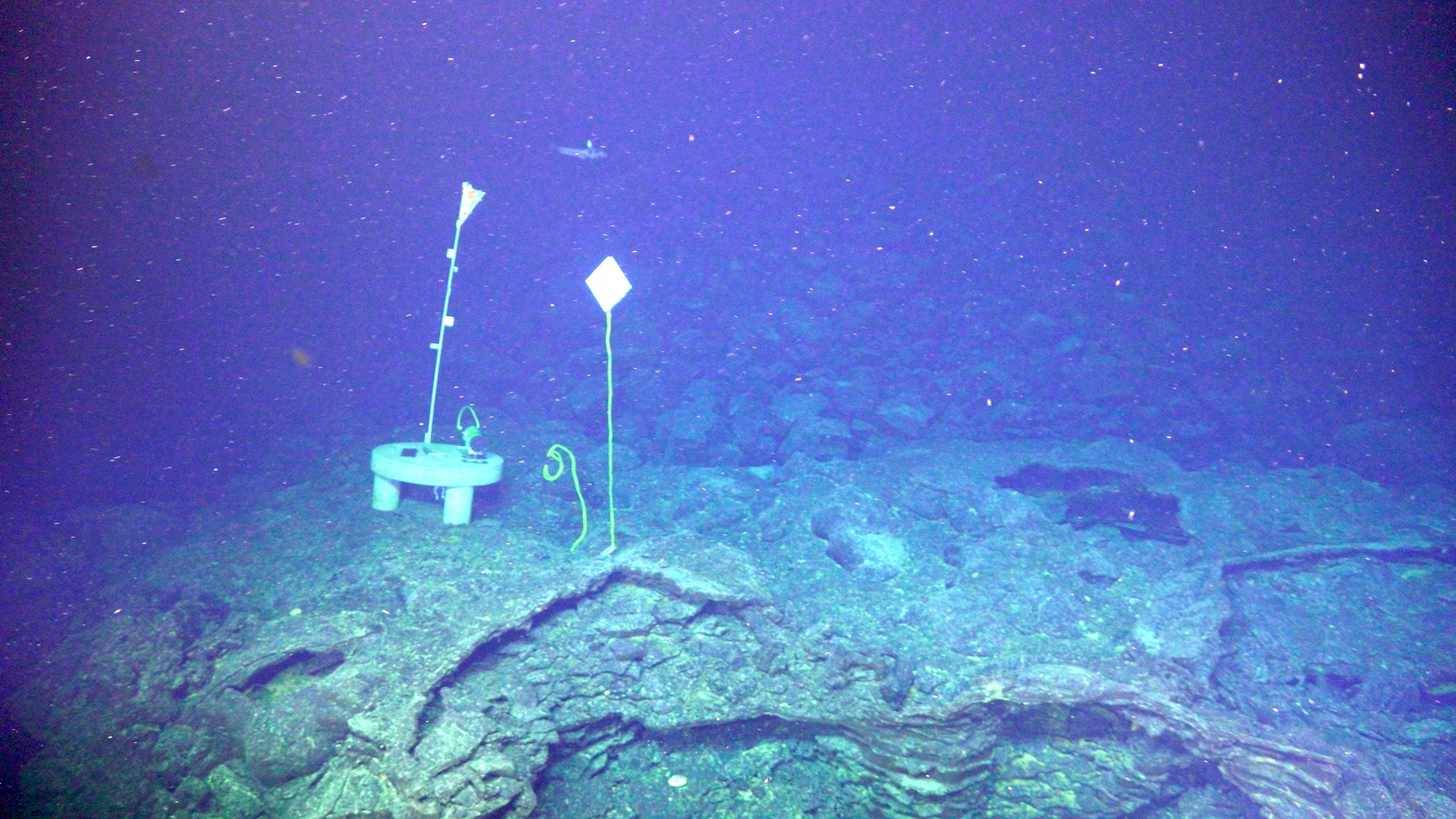

Underwater volcano off Oregon coast likely won't erupt until mid-to-late 2026

Underwater volcano off Oregon coast likely won't erupt until mid-to-late 2026

-

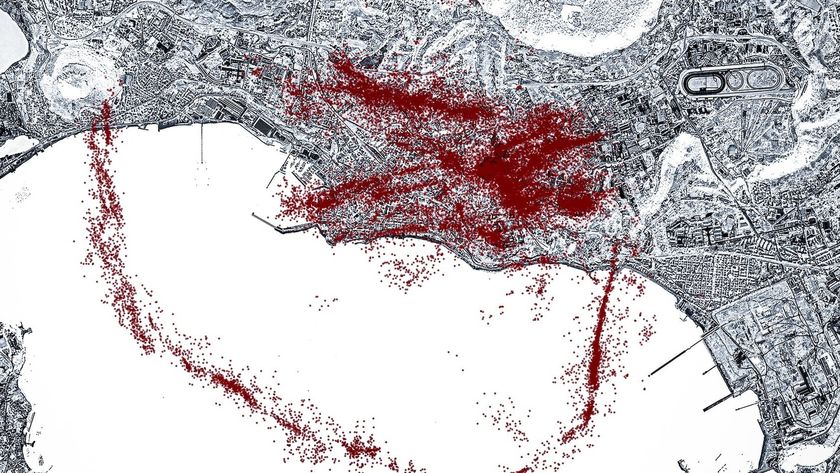

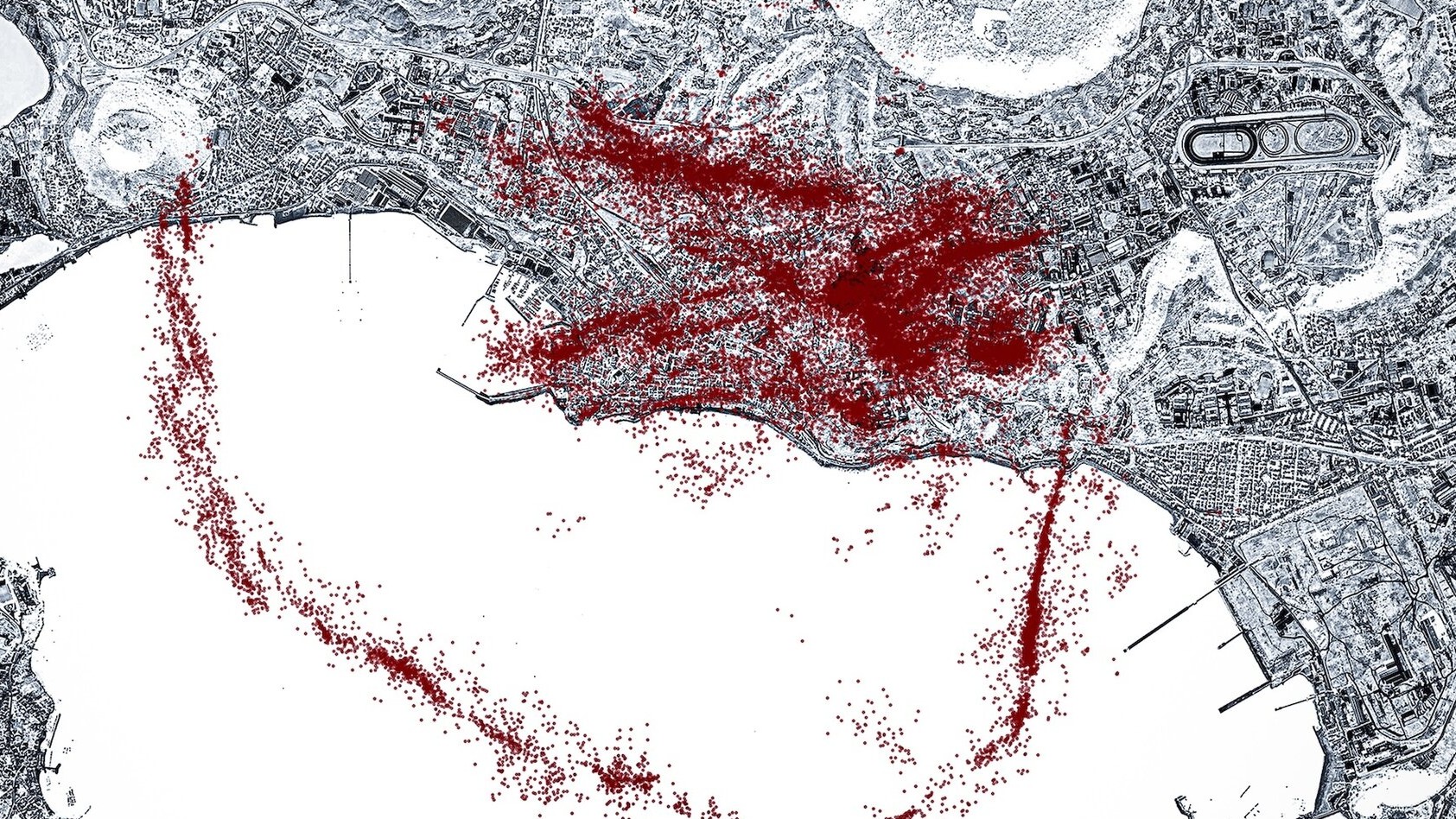

AI reveals hidden 'ring fault' that is unleashing earthquakes at Italy's Campi Flegrei volcano

AI reveals hidden 'ring fault' that is unleashing earthquakes at Italy's Campi Flegrei volcano

Almost immediately, though, the mountain started to reform, starting as a lava dome perched in the midst of this amphitheater. Over the years, the Institute of Volcanology and Seismology in Kamchatka, part of the Russian Academy of Sciences, has monitored the mountain's growth with fieldwork, web cameras and observation flights. A series of photographs taken from flights between 1949 and 2017 shows that the volcano has nearly reached its previous height, the researchers reports in 2020. Between 1956 and 2017, the researchers found, the mountain added 932,307.2 cubic feet (26,400 cubic meters) of rock per day, on average, the researchers found.

"The most surprising thing was the fast growth of the new volcanic edifice," study co-authors Alexander Belousov and Marina Belousova, both volcanologists at the Institute of Volcanology, told Live Science in an email.

The volcano now produces a couple of explosive eruptions a year, on average. The late-November event featured not only a billowing ash cloud, but also hot avalanches of gas and rock known as pyroclastic flows, Smithsonian's Global Volcanism Program reported Dec. 2.

As the volcano reaches its original height, the stability of its slopes is an important question, Belousov and Belousova told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over."It is known that similar edifices located inside horseshoe-shaped craters can experience one more large scale collapse and, as a result, a large scale explosive eruption," they said.

The flyover images reviewed in 2020 showed that the volcano not only sends out explosive clouds of ash and gas, but that it grows by what scientists called effusive eruptions: non-explosive flows of lava. The first of these was visible in 1977. Over time, this lava has become less rich in the mineral silica and less viscous, or goopy. Layers of this effusive lava have built up to turn Bezymianny back into a cone-shaped stratovolcano.

RELATED STORIES—Watch an Icelandic volcano's crater collapse

—'Like a sudden bomb': See photos from space of Ethiopian volcano erupting for first time in 12,000 years

—An Iranian volcano appears to have woken up — 700,000 years after its last eruption

Researchers are still monitoring the mountain from the ground as well as by satellite, Belousov and Belousova said. Though each volcano has its own trajectory, there are many volcanoes around the world that have experienced collapse and regrowth, such as Mount St. Helens in the U.S.

"The collected dataset is very important because the obtained knowledge allows volcanologists all over the world to make long-term forecasts of the behavior of different volcanoes which experienced large-scale collapses in their history," the researchers said.

Stephanie PappasSocial Links NavigationLive Science Contributor

Stephanie PappasSocial Links NavigationLive Science ContributorStephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Scientists discover new way to predict next Mount Etna eruption

Scientists discover new way to predict next Mount Etna eruption

Underwater volcano off Oregon coast likely won't erupt until mid-to-late 2026

Underwater volcano off Oregon coast likely won't erupt until mid-to-late 2026

AI reveals hidden 'ring fault' that is unleashing earthquakes at Italy's Campi Flegrei volcano

AI reveals hidden 'ring fault' that is unleashing earthquakes at Italy's Campi Flegrei volcano

'New' island emerges from melting ice in Alaska

'New' island emerges from melting ice in Alaska

Eruptions of ocean volcanoes may be the echoes of ancient continental breakups

Eruptions of ocean volcanoes may be the echoes of ancient continental breakups

Extreme 'paradise' volcano in Costa Rica is like a piece of ancient Mars on our doorstep

Latest in Volcanos

Extreme 'paradise' volcano in Costa Rica is like a piece of ancient Mars on our doorstep

Latest in Volcanos

'Like a sudden bomb': See photos from space of Ethiopian volcano erupting for first time in 12,000 years

'Like a sudden bomb': See photos from space of Ethiopian volcano erupting for first time in 12,000 years

Eruptions of ocean volcanoes may be the echoes of ancient continental breakups

Eruptions of ocean volcanoes may be the echoes of ancient continental breakups

Underwater volcano off Oregon coast likely won't erupt until mid-to-late 2026

Underwater volcano off Oregon coast likely won't erupt until mid-to-late 2026

Extreme 'paradise' volcano in Costa Rica is like a piece of ancient Mars on our doorstep

Extreme 'paradise' volcano in Costa Rica is like a piece of ancient Mars on our doorstep

Glowering 'skull' stares upward from a giant volcanic pit in the Sahara

Glowering 'skull' stares upward from a giant volcanic pit in the Sahara

Scientists discover new way to predict next Mount Etna eruption

Latest in News

Scientists discover new way to predict next Mount Etna eruption

Latest in News

This bright star will soon die in a nuclear explosion — and could be visible in Earth's daytime skies

This bright star will soon die in a nuclear explosion — and could be visible in Earth's daytime skies

The Arab region — a swath from Morocco to the United Arab Emirates — just had its hottest year on record

The Arab region — a swath from Morocco to the United Arab Emirates — just had its hottest year on record

Russia's Bezymianny volcano blew itself apart 69 years ago. It's now almost completely regrown.

Russia's Bezymianny volcano blew itself apart 69 years ago. It's now almost completely regrown.

Gray hair may have evolved as a protection against cancer, study hints

Gray hair may have evolved as a protection against cancer, study hints

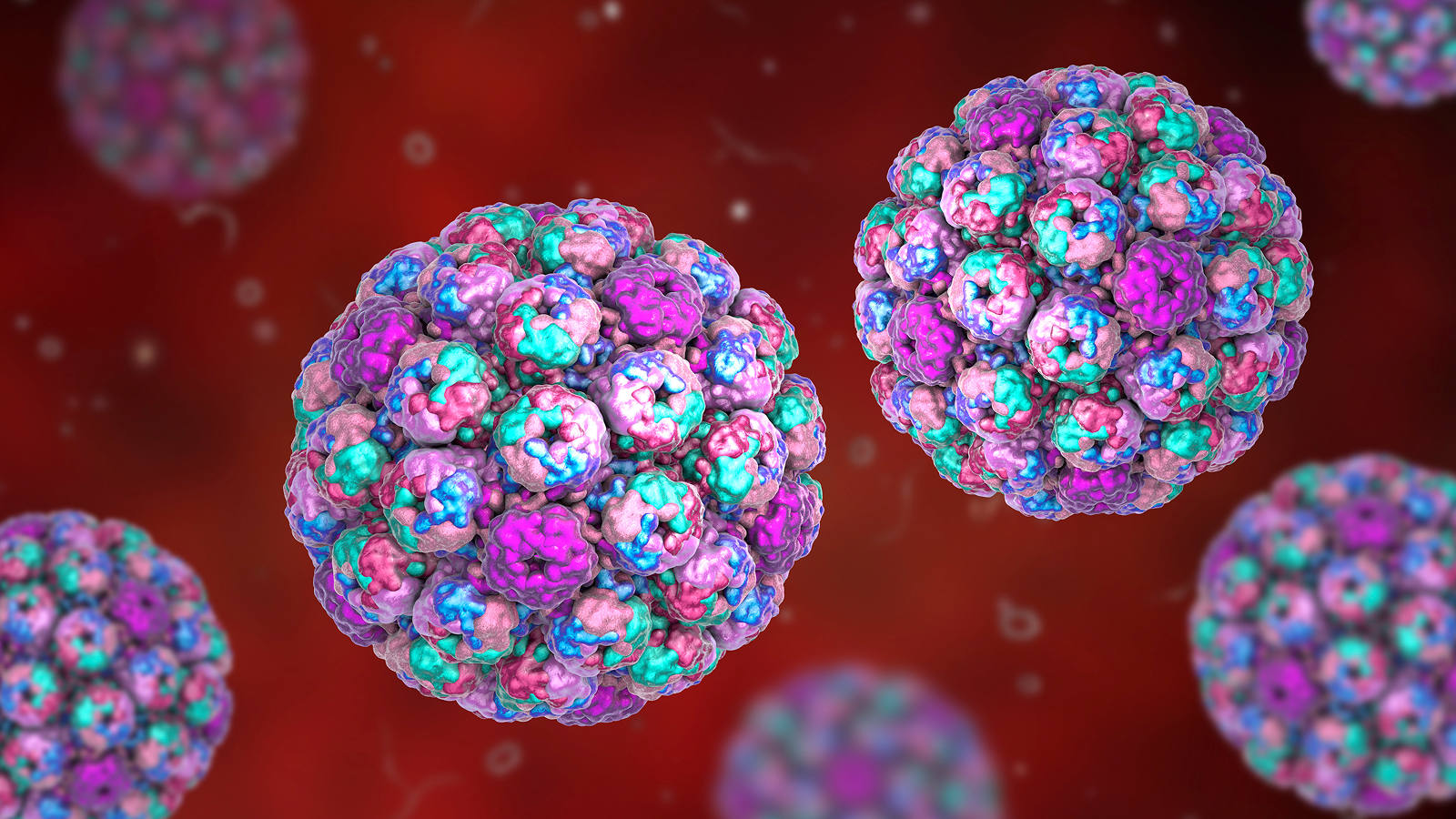

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

How to find the 'Christmas Star' — and what it really is

LATEST ARTICLES

How to find the 'Christmas Star' — and what it really is

LATEST ARTICLES 1This bright star will soon die in a nuclear explosion — and could be visible in Earth's daytime skies

1This bright star will soon die in a nuclear explosion — and could be visible in Earth's daytime skies- 2The Arab region — a swath from Morocco to the United Arab Emirates — just had its hottest year on record

- 3Earth's crust hides enough 'gold' hydrogen to power the world for tens of thousands of years, emerging research suggests

- 4Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

- 5Gray hair may have evolved as a protection against cancer, study hints