Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025: Your daily feed of the biggest discoveries and breakthroughs making headlines.

News By Tia Ghose, Patrick Pester last updated 10 December 2025When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

(Image: © NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Leah Hustak (STScI))

(Image: © NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Leah Hustak (STScI))

Here's the biggest science news you need to know.

- NASA's James Webb Space Telescope spots the earliest supernova on record.

- Humans couple up like meerkats according to a monogamy "league table."

- Researchers capture X-ray image of Comet 3I/ATLAS, revealing faint emission structure.

Latest science news

Refresh Get notified of updates 2025-12-10T23:54:09.577ZSo long, and thanks for all the fish!

2025-12-10T23:47:52.986ZSperm donor gives 200 children rare cancer mutation

A sperm donor from Denmark who fathered around 200 children passed on a rare cancer-causing mutation to many of them. Some of the children conceived with his sperm have already died.

The disturbing case of "donor 7069" was made by the EBU Investigative Journalism Network, a consortium of journalists from across Europe who do cross-border investigations.

The man, known as "Kjeld," began donating sperm as a student and continued to do so for 17 years. He carries a mutation in a gene known as TP53, which codes for the tumor suppressor protein p53. This protein works by enabling DNA repair and by preventing uncontrolled cell division, Ars Technica reported. People inherit one copy of TP53 from each parent, but inheriting a dysfunctional copy leads to Li-Fraumeni syndrome, which comes with a 90% chance of developing cancer by age 60. (As an aside, elephants, which very rarely get cancer, inherit 20 copies of TP53 from each parent.)

The man's sperm passed all the initial screenings, and rare mutations such as this are not typically screened for when it comes to sperm donation.

Many European countries have caps on how many children can be conceived from a single sperm donor, but this man's sperm was sold across 14 countries to 67 clinics, which meant those limits often didn't apply. In Denmark alone, "Kjeld" fathered at least 49 children up until 2013, despite a non-binding cap of 25 children being in place at the time, according to the EBU story.

The doctors who revealed the case are currently trying to track down all the children conceived with Kjeld's sperm and to inform them of the greater cancer risk.

Tia GhoseEditor-in-Chief (Premium)

2025-12-10T22:25:29.589Z

Tia GhoseEditor-in-Chief (Premium)

2025-12-10T22:25:29.589Z

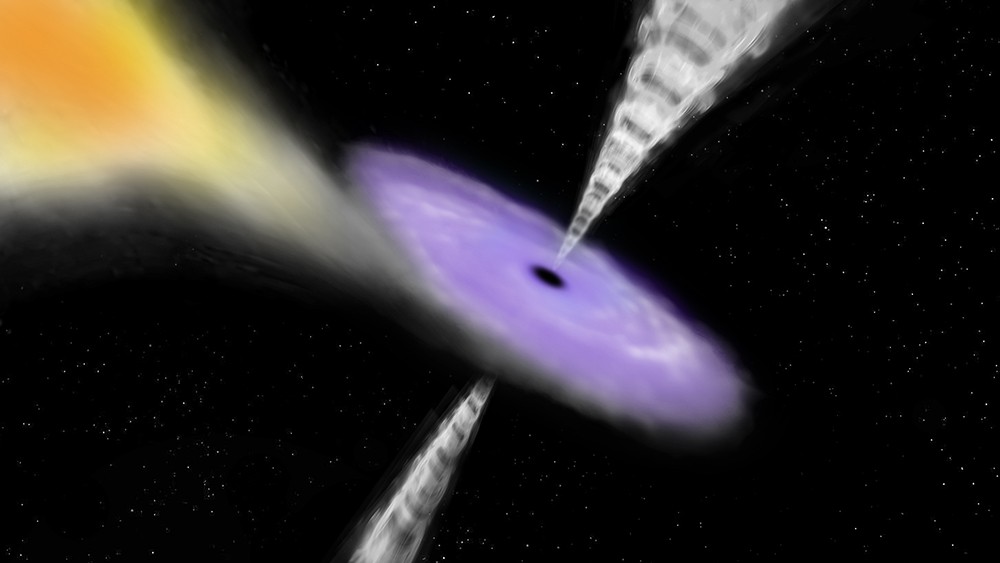

Spaghetti for two

In 1999, astronomers saw a deep space object go haywire. Watching with the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the team saw a well-known X-ray source called XID 925 suddenly brighten by nearly 30-fold, then start to fade again.

Scientists have struggled to explain the event for decades, but now — according to research accepted for publication in the journal The Innovation — there's a solution that fits the data nicely: A hapless star was shredded into stellar spaghetti by not one, but two black holes in the same region of space.

How does that all work? Physicist and Live Science contributor Paul Sutter explains in his latest story.

Brandon SpecktorSpace and Physics editor

2025-12-10T21:47:10.298Z

Brandon SpecktorSpace and Physics editor

2025-12-10T21:47:10.298Z

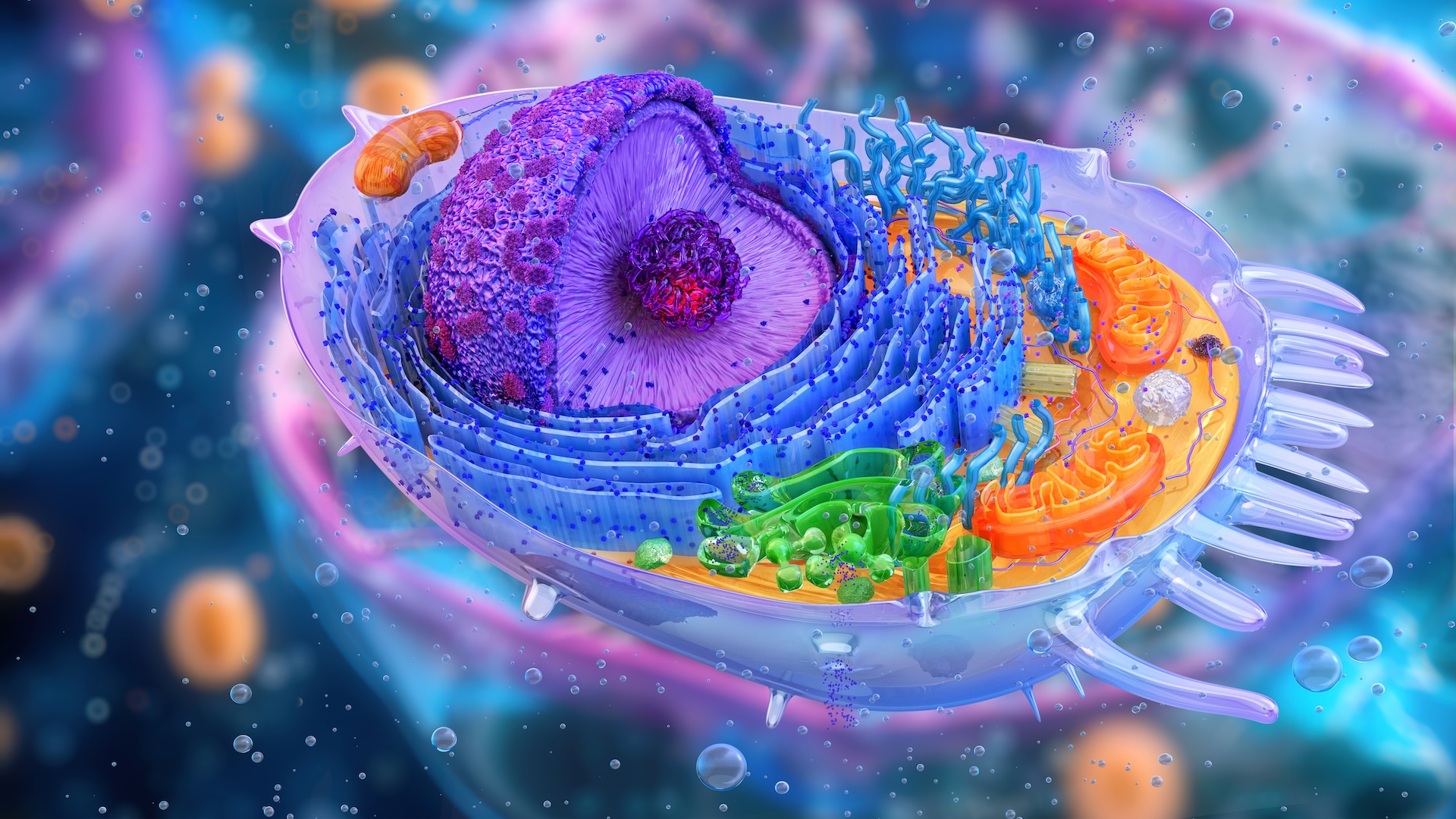

When did complex life evolve?

Complex life may have evolved more than 1 billion years earlier than previously thought, a new Nature study suggests.

Previously, scientists thought that the first eukaryotes, or cells that include a nucleus, cell membrane and organelles, first emerged around 2 billion years ago. The new study looked at the genomes of a wide range of organisms from across the tree of life. They used gene duplication events, in which sections of DNA are doubled, to calibrate a molecular clock.

Their estimates suggest that the first cells with nuclei emerged 2.9 billion years ago — roughly a billion years before the organisms that would give rise to mitochondria were assimilated by eukaryotes. Scientists believe that our mitochondria — cellular powerhouses that are responsible for "breathing" oxygen — evolved from primitive bacteria and were absorbed via endosymbiosis.

"The process of cumulative complexification took place over a much longer time period than previously thought," study co-author Gergely Szöllősi, Head of the Model-Based Evolutionary Genomics Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST), said in a statement.

Intriguingly, the rise in mitochondria corresponds to a rise in atmospheric oxygen, during what's known as the "Great Oxidation Event." The findings suggest ancient life forms were accomplishing complex cellular functions in oceans devoid of oxygen, according to the statement. It's also more evidence that life shapes the geochemistry of the planet.

Meanwhile, primitive life has been here almost since the beginning. The planet is around 4.5 billion years old, and the last universal common ancestor of all living organisms, known as LUCA, emerged 4.2 billion years ago. And LUCA wasn't alone; there were other viruses and bacteria filling its primeval ecosystem, genetic traces suggest. That means life likely emerged even earlier than LUCA, but just didn't pass on its genes to any creatures living today.

Tia GhoseEditor-in-Chief (Premium)

2025-12-10T20:26:56.594Z

Tia GhoseEditor-in-Chief (Premium)

2025-12-10T20:26:56.594Z

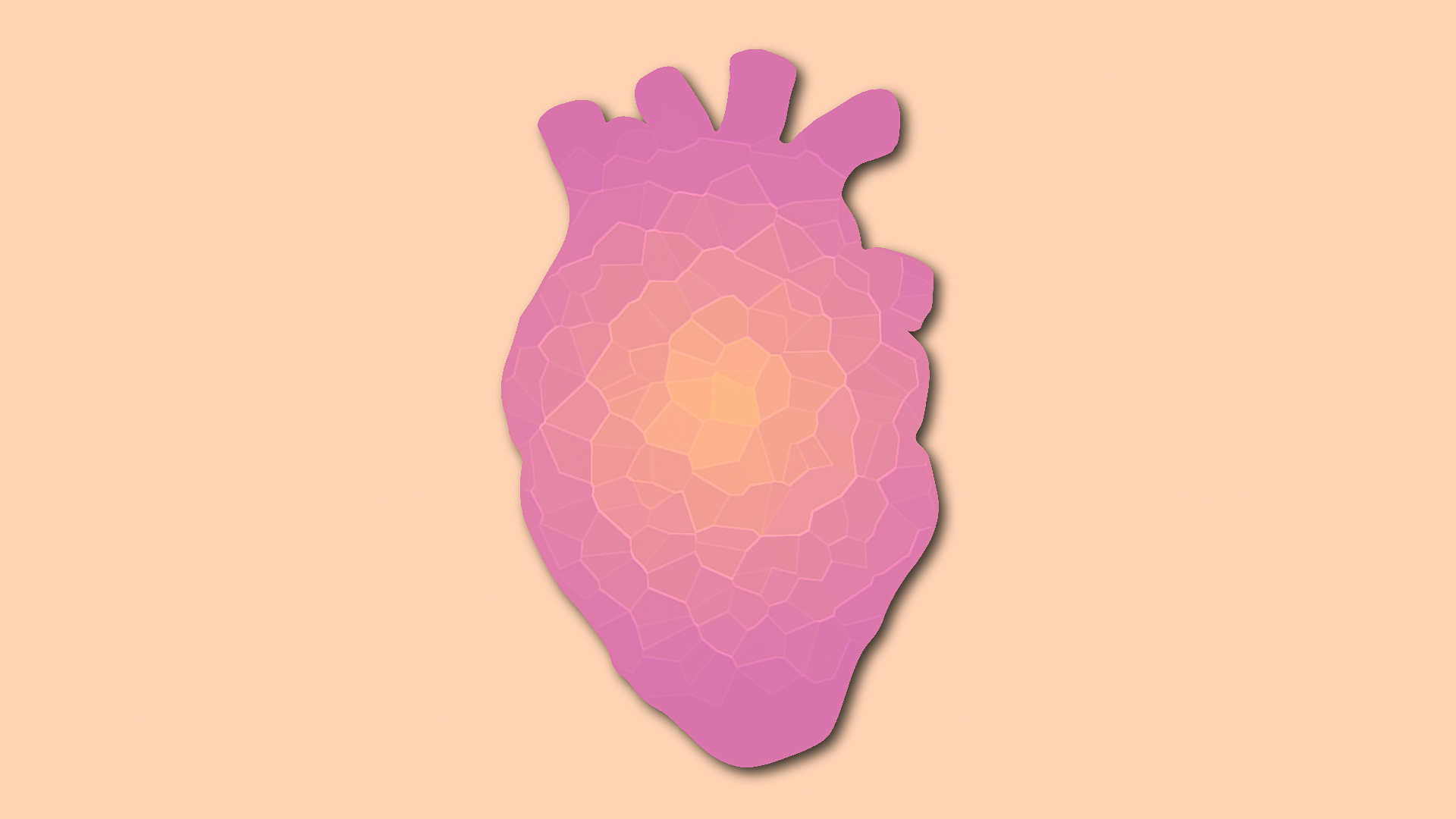

Rare side effect of COVID vaccines unraveled

Myocarditis — inflammation of the heart muscle — is a rare side effect of COVID-19 vaccines, specifically those made using mRNA technology. A new study may have pinpointed how this side effect occurs and how to potentially stop it in its tracks, STAT reported.

"I want to emphasize this is very, very rare. This study is purely to understand why," the senior study author told STAT. As mRNA medicines, especially vaccines, face scrutiny and funding cuts from the U.S. federal government, researchers must carefully navigate how to study and call attention to aspects of the technology that still need improvement without putting fuel on the fire of anti-mRNA conspiracy theories.

The new study uncovered two immune signaling proteins, called cytokines, that appear in higher quantities in the blood of vaccine recipients with myocarditis than in those who didn't experience the side effect. The heart-damaging effects of these cytokines — CXCL10 and interferon-gamma — can be blocked with antibodies and with an anti-inflammatory compound found in soybeans, the study authors found in lab-dish experiments and in mice with myocarditis.

Notably, the myocarditis side effect is most often seen in teen boys and young men. The soybean compound, which is chemically similar to estrogen, lends credence to the idea that the female sex hormone might protect against the effect, Scientific American reported.

More work is needed to translate these findings into humans and to fully understand why mRNA vaccines, specifically, sometimes trigger this chain reaction. Read more in STAT, SciAm, or in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Nicoletta LaneseHealth Channel Editor

2025-12-10T18:00:51.643Z

Nicoletta LaneseHealth Channel Editor

2025-12-10T18:00:51.643Z

Until tomorrow

2025-12-10T17:58:24.054ZEurope gets tougher on greenhouse gas emissions

The European Union has agreed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 90% by 2040, Reuters reports.

The new, legally binding climate target aims to cut emissions from European industries by 85%. The remaining 5% will come from the purchase of foreign carbon credits. Essentially, Europe will pay developing countries to cut emissions on its behalf.

The European Parliament and E.U. country negotiators agreed on the climate deal in the early hours of this morning (Dec. 10).

The target is among the most ambitious in the world, though still not as strong as what the E.U.'s climate science advisors recommended. It's also meant to help ensure that Europe reaches its 2050 net-zero emissions pledge, according to Reuters.

The E.U. wants to become the "first climate-neutral continent," where the amount of greenhouse gas it emits into the atmosphere is offset by the amount it removes, for example, through natural and artificial carbon sinks.

Greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide trap heat in the atmosphere by absorbing radiation, and thereby raise global temperatures. The consequences of global warming include weather pattern changes, sea level rise, compromised food supply, and a host of other issues that will affect the lives of billions.

Patrick PesterTrending News Writer

2025-12-10T17:04:45.624Z

Patrick PesterTrending News Writer

2025-12-10T17:04:45.624Z

The next naked-eye supernova?

Astronomers have taken a fresh look at an infamous star system veering toward catastrophe — and found the best evidence yet that it's due for a historic supernova explosion.

The binary star system V Saggitae, located 10,000 light-years from Earth, contains a white dwarf (the smoldering core of a dead star) and a larger, still-burning companion star whipping around one another every 12 hours. The dwarf star regularly rips material off its companion, triggering frequent X-ray flashes as thermonuclear reactions erupt on the white dwarf's surface.

The new research, based on 120 days of observations, confirms that a double-whammy light show is currently in production at V Saggitae. First, we'll see a nova: a bright explosion unleashed after the white dwarf has consumed too much of its companion, and violently ejects that excess matter into space. Then, once the two stars finally collide, the main event: A supernova explosion so bright "it'll be visible from Earth even in the daytime," study co-author Pablo Rodríguez-Gil told Live Science.

When will this historic daytime supernova occur? Contributor Ivan Farkas breaks down scientists' best estimates in his new story for Live Science.

Brandon SpecktorSpace and Physics editor

2025-12-10T16:08:23.359Z

Brandon SpecktorSpace and Physics editor

2025-12-10T16:08:23.359Z

Neanderthal Prometheus

Researchers in England have discovered the earliest and clearest evidence of purposeful fire-making in the world, settling — for now — a long-running debate about human control of fire. And it turns out that it was Neanderthals, not humans, who invented the technology.

Archaeologists identified a series of tiny pyrite chips as the "smoking gun" of fire control at Barnham, an ancient pond site in Suffolk that was occupied more than 400,000 years ago. Neanderthals likely imported the pyrite from elsewhere in England to strike against flint, making sparks.

Read my coverage of the new study to find out why archaeologist Nick Ashton called it "the most exciting discovery in my 40-year career."

Kristina KillgroveStaff Writer

2025-12-10T16:04:45.341Z

Kristina KillgroveStaff Writer

2025-12-10T16:04:45.341Z

Monogamy 'league table'

What do humans, meerkats and beavers have in common? We all tend to be relatively monogamous.

Mark Dyble, an evolutionary anthropologist at the University of Cambridge, has unveiled a monogamy "league table" after investigating the varying levels of exclusive mating in different animals.

Humans came out with a monogamy rate of 66%, which was closer to that of meerkats (60%) and beavers (73%) than most of our primate cousins, according to the researcher's findings, published today in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Chimpanzees are one of our closest living relatives, yet the study highlighted that they have a more polygynandrous approach to mating. Males and females mate with multiple different partners, giving them a monogamy rate of 4%.

California deermice topped the table with a monogamy rate of 100%. This species pairs for life as part of its mating strategy. Scotland’s Soay sheep, on the other hand, were at the bottom of the table. Ewes (females) of this breed mate with several rams (males), resulting in a monogamy rate of 0.6%.

"There is a premier league of monogamy, in which humans sit comfortably, while the vast majority of other mammals take a far more promiscuous approach to mating," Dyble said in a statement.

Dyble used a computer model to calculate the scores, based on sibling data from genetic studies and known reproductive strategies. It's worth noting that a higher or lower monogamy rate doesn't mean that a species is any more or less successful. The score is merely an indicator of reproduction habits.

Of course, humans are a varied bunch, and we're well known for having a variety of different mating norms.

Patrick PesterTrending News Writer

2025-12-10T15:26:27.961Z

Patrick PesterTrending News Writer

2025-12-10T15:26:27.961Z

Life on the wall

Hadrian's Wall in northern England marked the border of the Roman Empire for nearly 300 years. But far from a "Game of Thrones"-style wall, where isolated (and cold) soldiers pee off the end of the world, experts told Live Science the Roman frontier was actually a diverse region of danger, boredom and even opportunity. (It was definitely cold though.)

To find out more about life on the edge of the Roman world, read the full story here.

James PriceProduction Editor

2025-12-10T14:33:11.079Z

James PriceProduction Editor

2025-12-10T14:33:11.079Z

Regrowing volcano

Bezymianny volcano blew itself apart in 1956. Now, thanks to frequent eruptions, it's almost completely regrown, Live Science contributor Stephanie Pappas reports.

Bezymianny is an active cone-shaped volcano on the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Russian Far East. Last month, the volcano ejected a massive ash cloud that rose 32,800 feet (10 kilometers) into the air.

Researchers say that eruptions like this spurred the volcano to reform, and draw closer to its pre-1950s height of at least 10,213 feet (3,113 meters). The volcano is currently 9,455 feet (2,882 m), according to the Smithsonian's Global Volcanism Program.

Read the full story here.

2025-12-10T14:12:48.206ZLive Science news roundup

- Gray hair may have evolved as a protection against cancer, study hints

- 'It is simply too hot to handle': 2024 was Arab region's hottest year on record, first-of-its-kind climate report reveals

- Rare 'sunglint' transforms Alabama River into a giant 'golden dragon' — Earth from space

- This bright star will soon die in a nuclear explosion — and could be visible in Earth's

Supernova surprise

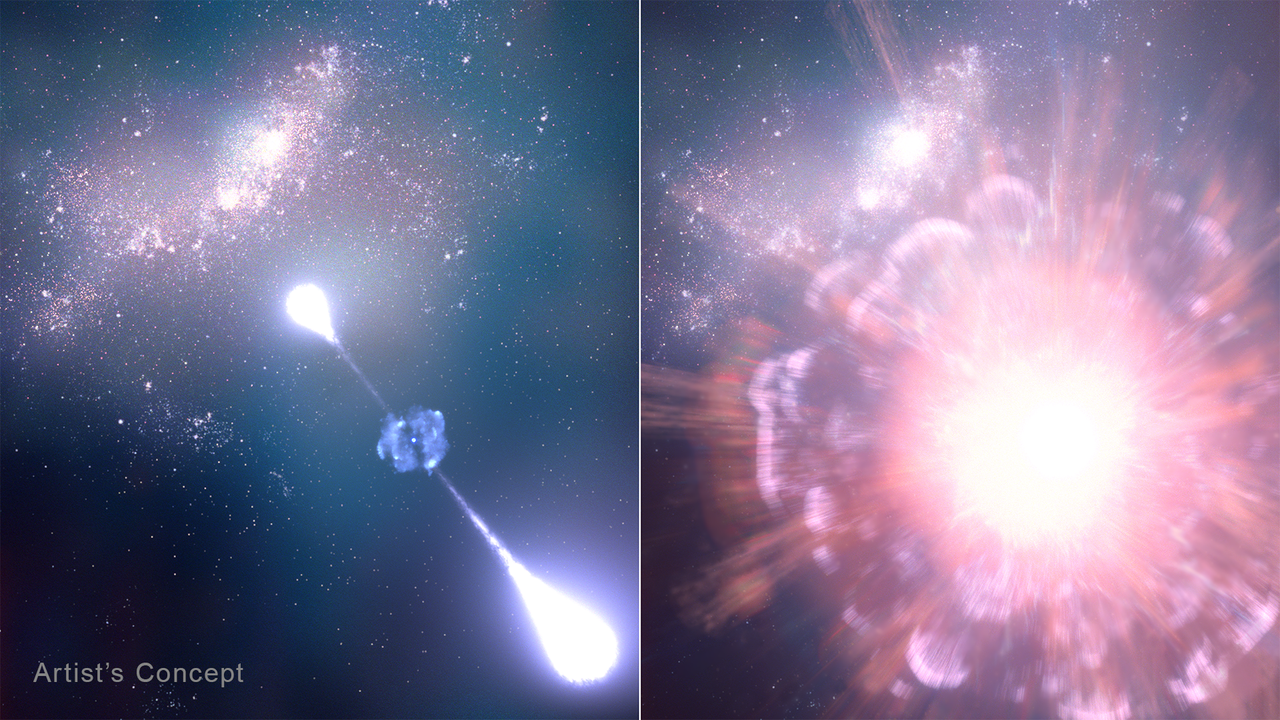

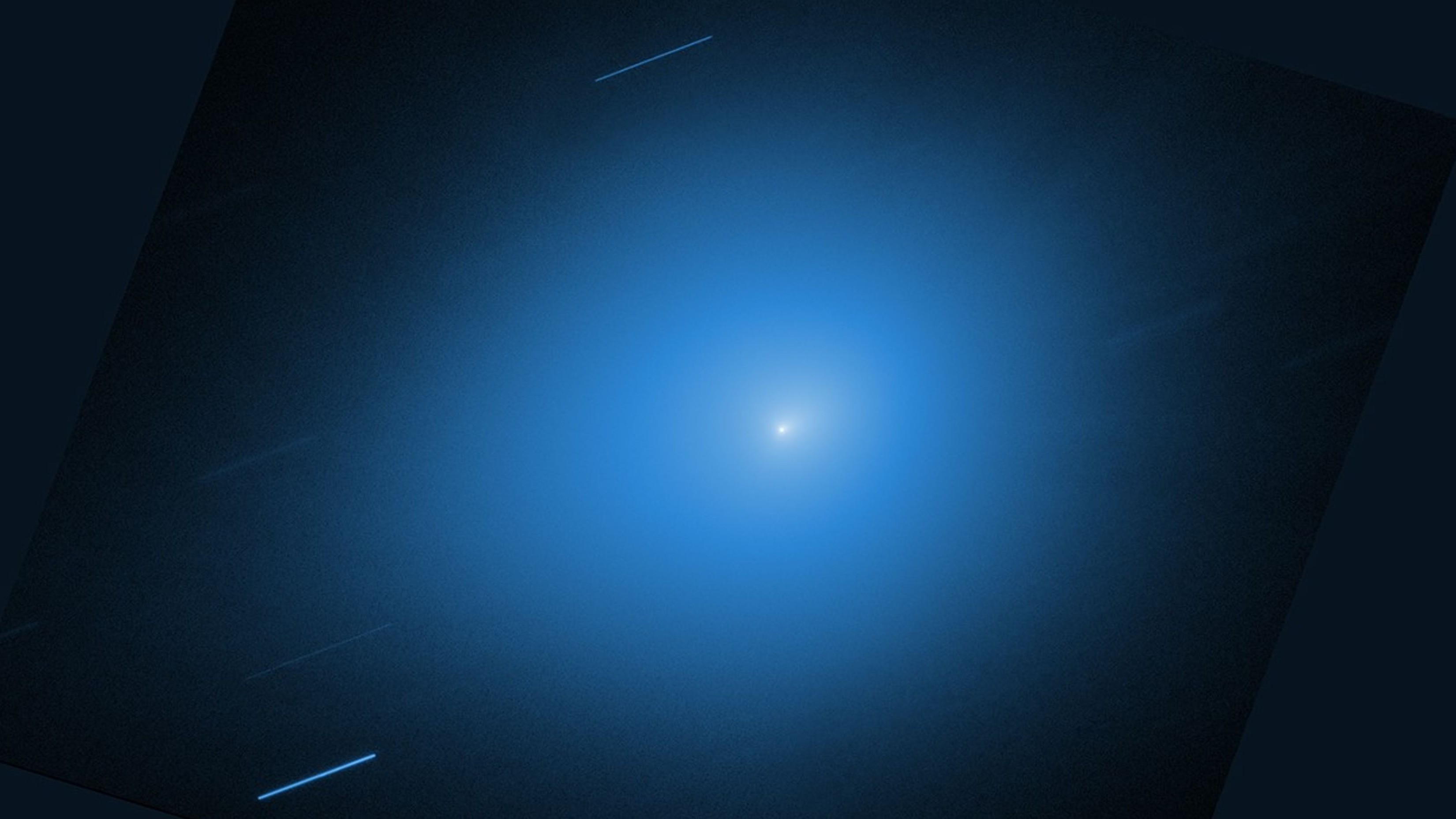

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has identified the earliest supernova on record, according to a statement released by the space agency yesterday.

The ancient and distant supernova exploded when the universe was in its infancy at just 730 million years old. For context, the universe is thought to be around 13.8 billion years old.

JWST turned its attention to the supernova in July after an international group of telescopes detected a rare gamma-ray burst (bright flash of light) in March, according to the statement.

"Only Webb could directly show that this light is from a supernova — a collapsing massive star," Andrew Levan, an astronomer at Radboud University in the Netherlands and the University of Warwick in the U.K., said in the statement.

"This observation also demonstrates that we can use Webb to find individual stars when the universe was only 5% of its current age," Levan added.

Surprisingly, the supernova looked very similar to modern supernovae that have occurred much closer to Earth. Researchers will need to collect more data to explore why this might be the case.

Aurora no-show

Good morning, science fans! Patrick here to launch another day of our science news blog coverage.

Yesterday's northern lights forecast turned out to be a bit of a let-down for skywatchers.

NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center had issued a strong G3 geomagnetic storm watch for Tuesday, which had the potential to produce visible auroras over many U.S. states from the lower Midwest to Oregon.

However, this storm was expected to be triggered by a blast of plasma from the sun (coronal mass ejection, or CME), which didn't arrive as forecast.

Live Science's sister site Space.com reports that the CME only brushed Earth or missed us altogether.

Space weather forecasters are still seeing moderate to high solar activity, but for now, aurora activity is likely to be limited.

Patrick PesterTrending News Writer

2025-12-10T00:06:20.905Z

Patrick PesterTrending News Writer

2025-12-10T00:06:20.905Z

Catch you on the flip side!

2025-12-09T23:06:34.771ZTop Martian priorities

Our top priority when humans reach Mars should be to hunt for past or present life on the Red Planet, a new report from leading U.S. scientists argues.

The report, released by the National Academy of Sciences today (Dec. 9), lays out a road map of scientific priorities for the (hopefully) coming crewed mission to Mars.

That, of course, could be years away: NASA doesn't anticipate humans reaching Mars before the 2030s. But the gears are in motion. NASA’s Artemis moon mission could launch as early as this February, after years of delays. Artemis was always planned as a stepping stone to an eventual Mars mission.

If we do make it to the Red Planet in the next decade, we should also look for evidence of CO2 and water cycles, investigate the geological history of Mars, and study the physiological and psychological effects of both spaceflight and the Martian environment on potential astronauts living there, the report says.

Lower down on the list, scientists say we should explore Mars searching for resources we could exploit for future colonies, analyze the effects of the Martian environment on DNA and its replication, and characterize microbial communities that may be brought along for the ride through the solar system. As part of the new road map, they also lay out which types of measurements and instrumentation may be required to address each of those priorities.

It's a big and somewhat daunting list, but it's hard to imagine investing the staggering amount of money and technological innovation required to reach the Martian surface if we're not going to learn as much as we can from the process.

Tia GhoseEditor-in-Chief (Premium)

2025-12-09T22:14:17.881Z

Tia GhoseEditor-in-Chief (Premium)

2025-12-09T22:14:17.881Z

RFK's FDA takes aim at RSV preventative treatments

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has informed pharma executives that it will be reevaluating already-approved treatments designed to protect infants from RSV, according to exclusive reporting from Reuters.

RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) is an infection that spreads seasonally and is particularly dangerous to young children, standing as the most common cause of hospitalization in infants. Annually, 100 to 300 children under 5 die from the infection in the U.S. To drive that number down, in recent years, scientists have invented, tested and earned FDA approval for antibody-based drugs that protect infants during RSV season. These treatments have been thoroughly researched in large clinical trials and shown to be both safe and effective at lowering the risk of serious RSV that requires a doctor's appointment, ER visit or hospitalization.

The treatments are recommended to all infants under 8 months old in their first RSV season, excluding babies whose mothers got an RSV vaccine before birth. (The vaccine prompts the mother to make antibodies that get passed to the baby.) Additionally, select kids with health conditions are recommended another dose during their second RSV season.

The antibody shots are sometimes lumped into conversations and controversy surrounding vaccines, despite not being vaccines themselves. They supply the body with ready-made antibodies; they do not teach the immune system to make its own, as a vaccine would.

The FDA has informed makers of the antibody drugs that it will be asking further safety questions about the treatments, and for now, it's unclear if that reevaluation might lead to changes in the drugs' availability or approval status.

What we do know is that the pattern is reminiscent of a move made by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last week, in which the agency overturned established guidance about the hepatitis B vaccine with no data suggesting they should make the change — and ample data suggesting they should not. Such moves align with the stance of health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who posits that the risks of many pharmaceutical products have not been properly studied and casts doubt on established science.

Learn more about the RSV antibody treatments here.

Nicoletta LaneseHealth Channel Editor

2025-12-09T21:21:05.472Z

Nicoletta LaneseHealth Channel Editor

2025-12-09T21:21:05.472Z

Ubiquitous cold virus may raise risk of bladder cancer

Cancer isn't infectious — but we now know that several types of infections do raise the risk of cancer down the line. Among the well-known microbes known to fuel cancer are HPV, the primary cause of cervical cancer; hepatitis B, which causes liver cancer; and Helicobacter pylori, which raises stomach cancer risk.

Live Science contributor Jennifer Zieba has a fascinating new piece on another cancer which may be fueled, at least in part, by past infection.

Although most of us have never heard about the virus, it is a common infection that tons of us get as kids. To learn more about the virus, and how researchers think it may raise cancer risk, read the full story here.

2025-12-09T20:21:44.631Z'Gold hydrogen' sufficient to power human civilization for 170,000 years

Staff writer Sascha Pare has a fascinating feature on the hunt for "gold hydrogen," or hydrogen that's naturally found in large quantities separate from natural gas.

Hydrogen could power a green economy, but the naturally occurring stuff has historically been found with natural gas, which produce greenhouse gases when burned. But a 2016 find in Mali changed our understanding of how much hydrogen is lurking in Earth's crust, and where it's likely to be found.

Read more to learn about this hydrogen "gold rush" in her Science Spotlight story here.

Tia GhoseEditor-in-Chief (Premium)

2025-12-09T18:36:32.105Z

Tia GhoseEditor-in-Chief (Premium)

2025-12-09T18:36:32.105Z

More parents refusing the vitamin K shot for their babies

New research in JAMA finds that more parents are opting out of giving their babies a recommended vitamin K shot at birth. And that puts babies at risk, experts say.

"We know unequivocally that infants that don't receive vitamin K are at significantly higher risk of getting serious bleeding," the lead study author told Scientific American.

All newborns are recommended to receive an injection of vitamin K, a nutrient that helps the body form blood clots. Older children and adults get vitamin K from their diets and their gut microbiomes, but babies are born with very little.

The nutrient doesn't easily pass through the placenta and babies' microbiomes are too immature to make it; breast milk also contains relatively little vitamin K, and regardless, vitamin K given to babies by mouth isn't absorbed well. That means babies are vulnerable to vitamin K deficiency, which can lead to dangerous bleeding, and in turn, permanent brain damage or death.

The one-time vitamin K shot protects babies from this deficiency extremely effectively and safely. Since universal administration of the vitamin was started in 1961, the U.S. has "nearly eliminated" vitamin K deficiency bleeding. But now, our numbers are slipping.

The JAMA analysis found that, between 2017 and 2024, the rate of vitamin K shot refusal has risen nearly 80%, with the proportion of newborns not given the shot rising from 2.92% to 5.18%.

Anecdotally, I've seen my share of breathless, online influencers spreading misinformation about vitamin K shots. Their efforts are closely tied to — if not indistinguishable from — the anti-vaccine movement, despite vitamin K shots not being vaccines. Often, the influencers promote unproven alternatives to the shot, which they personally happen to sell.

But to put it plainly: when vitamin K administration goes down, the rate of babies dying goes up. The new JAMA study calls attention to that disturbing trend. You can learn more about the vitamin K shot from the American Academy of Pediatrics and their informational site, Healthy Children.

Nicoletta LaneseHealth Channel Editor

2025-12-09T18:06:54.000Z

Nicoletta LaneseHealth Channel Editor

2025-12-09T18:06:54.000Z

Over and out

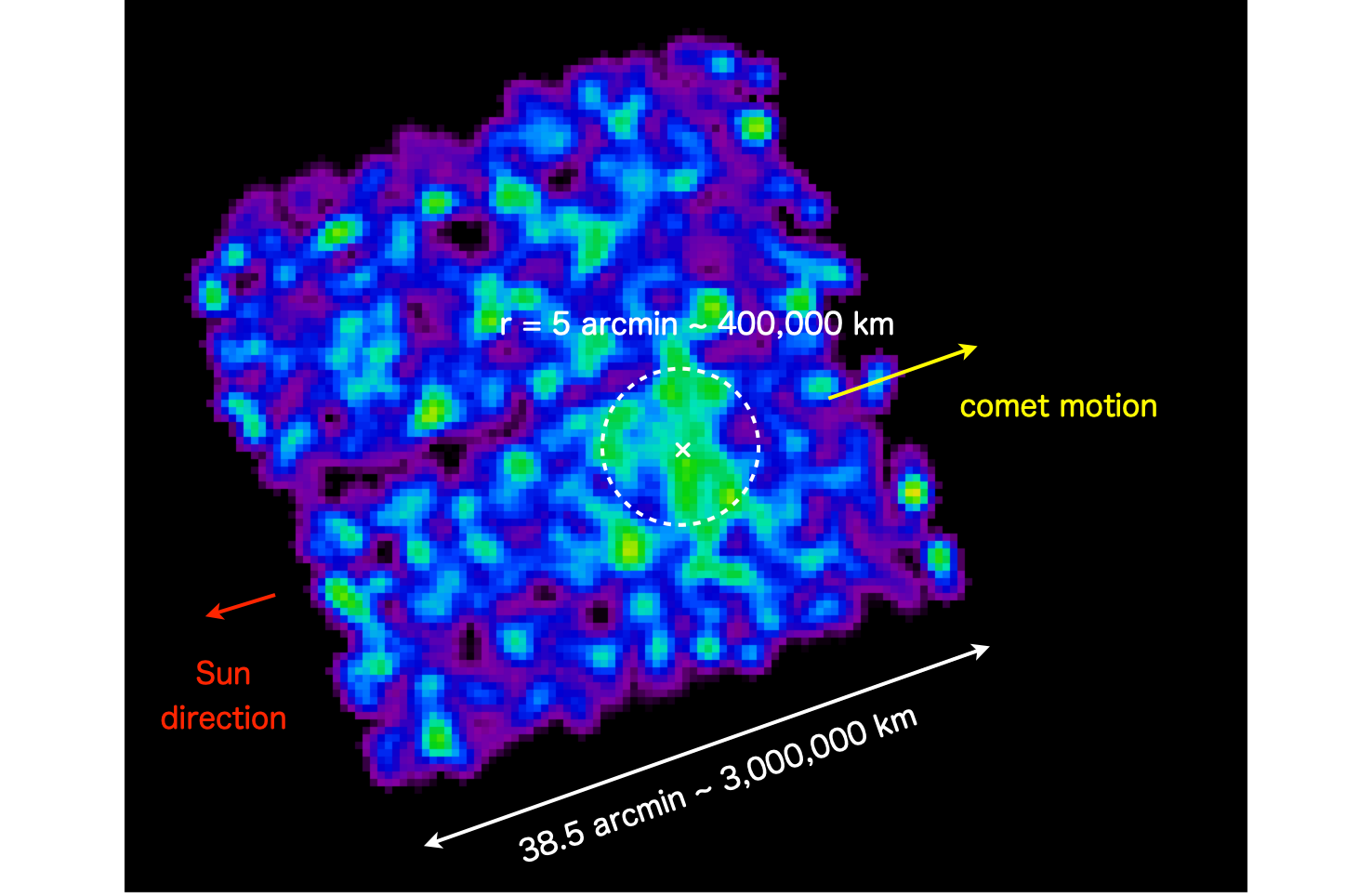

2025-12-09T18:02:32.217ZComet 3I/ATLAS gets an X-ray

Comet 3I/ATLAS has been viewed through an X-ray space telescope for the first time, revealing an X-ray glow stretching about 250,000 miles (400,000 kilometers) around the interstellar visitor.

This is the first time researchers have been able to detect X-rays emanating from an interstellar comet.

The comet was observed as part of the X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission (XRISM), a collaboration between the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA).

Researchers across the globe are scrambling to learn all they can about comet 3I/ATLAS before this rare interstellar visitor exits our solar system next year.

XRISM observed comet 3I/ATLAS between Nov. 26 and Nov. 28, just as the comet moved far enough away from the sun to be visible to the telescope’s instruments.

"Comets are enveloped by clouds of gas produced as sunlight heats and vaporizes their icy surfaces," XRISM representatives wrote in a statement. "When this gas interacts with the energetic stream of charged particles flowing from the Sun — the solar wind — a process called charge-exchange reaction occurs, producing characteristic X-ray emission."

The researchers described the glow in the X-ray image as a "faint emission structure" and said it was potentially the result of a diffuse cloud of gas.

However, the researchers also noted that instrumental effects such as vignetting or detector noise can create similar structures in images, so they'll have to do follow-up analysis to confirm whether the extensive emission structure belongs to the comet.

"Moving forward, the XRISM team will continue refining its data processing and analysis to further reveal the activity of this interstellar comet and the nature of its interaction with the solar wind," the representatives wrote.

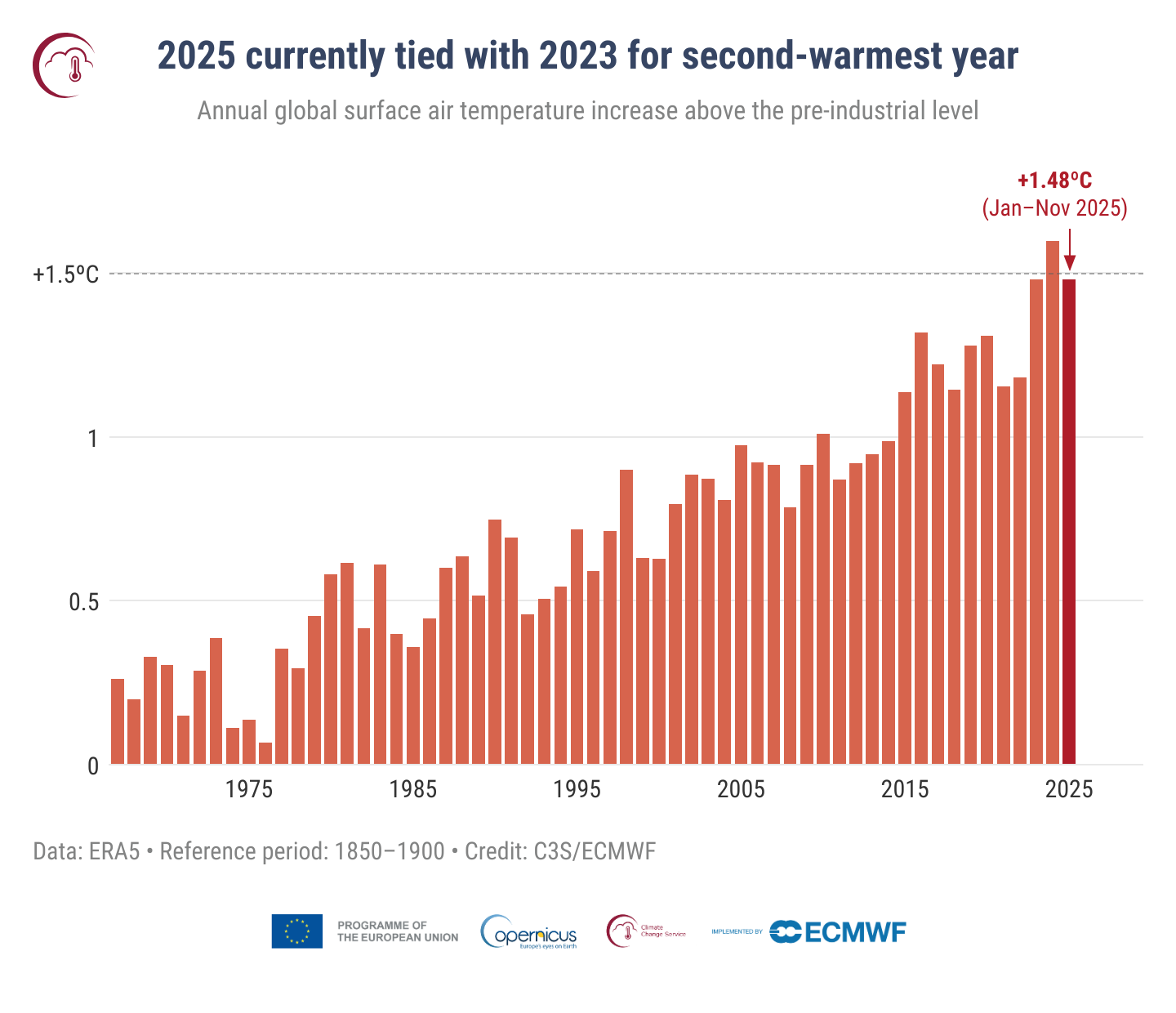

2025-12-09T16:40:08.515ZAnother climate milestone

2025 is set to tie for the second-warmest year on record, the European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service has announced.

As of November, this year is tied with 2023 for annual global surface temperature, but the temperature is slightly cooler than it was in 2024, the warmest year on record.

The latest data suggests that next month we'll be able to say that the last three years were the warmest on record — an ominous consequence of global warming.

Researchers measure global temperature rise above the estimated average temperature between 1850 and 1900, known as pre-industrial levels.

World leaders promised to limit this warming to preferably below 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius) and well below 3.6 F (2 C) in the 2015 Paris Agreement, adopted at the United Nations' COP21 climate conference. Unfortunately, they're failing.

"For November, global temperatures were 1.54 C above pre-industrial levels, and the three-year average for 2023–2025 is on track to exceed 1.5 C for the first time," Samantha Burgess, the strategic lead for climate at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, which implements the Copernicus program, said in a statement.

"These milestones are not abstract — they reflect the accelerating pace of climate change and the only way to mitigate future rising temperatures is to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions," Burgess added.

It's worth remembering that last month, climate deliberations at the COP30 conference in Brazil ended in an underwhelming compromise. The final text of the COP30 agreement didn't contain any clear mention of fossil fuels, which are the primary source of increased greenhouse gas emissions.

2025-12-09T15:28:31.827ZKick me with your best shot

75kg class head-on brawl! EngineAI T800 kicks the boss: Is this kick personal?#EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct pic.twitter.com/UCRrP0qBazDecember 6, 2025

EngineAI said that the purpose of the simulated fight was to counter claims that its latest model was a CGI creation, CNN reports.

While the T800 appears to have a decent kick, it doesn't go unnoticed that Tongyang was standing still, waiting patiently for his robot to strike.

With that in mind, don't expect to see robots beating UFC fighters anytime soon.

2025-12-09T14:44:47.318ZAuroras incoming

NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center has a strong G3 geomagnetic storm watch in place for today (Dec. 9), with the potential for visible auroras over many U.S. states from the lower Midwest to Oregon.

The geomagnetic storm is associated with the eruption of a solar flare on the sun, which is thought to have sent a blast of plasma (coronal mass ejection, or CME) toward Earth.

Space weather forecasters have been expecting the CME to clash with Earth's magnetic field and trigger the geomagnetic storm, along with the potentially visible auroras.

The CME could also have limited, minor effects on technological infrastructure, but this can usually be mitigated, according to the Space Weather Prediction Center.

2025-12-09T13:33:25.184ZA Christmas star

Jupiter is shining bright in the night sky this winter, with Live Science contributor Jamie Carter drawing comparisons between it and the "Star of Bethlehem."

Does this biblical star have any astronomical origins? Find out more by reading Carter's full story here.

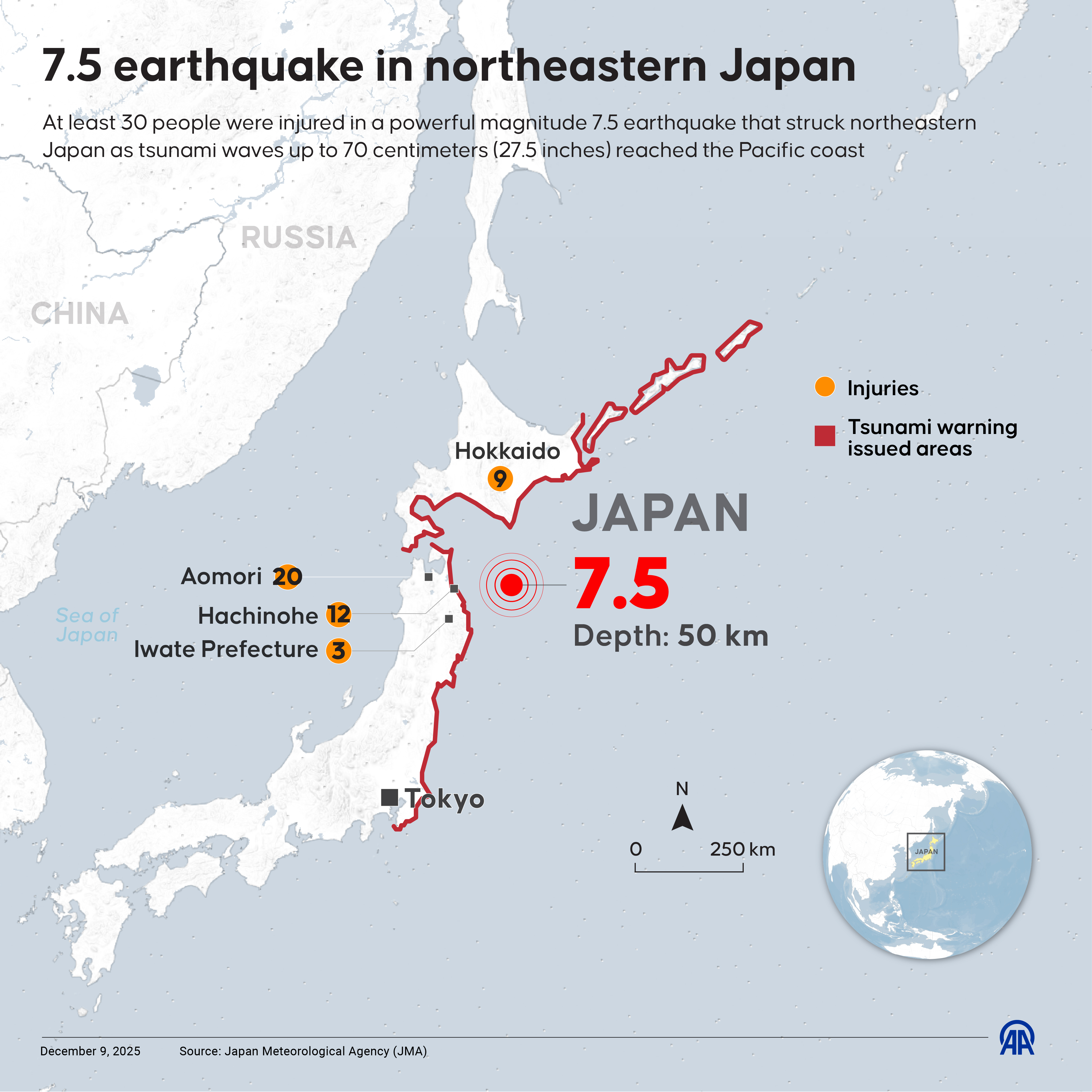

2025-12-09T12:52:02.767ZMegaquake advisory

Japan is now on "mega-quake" alert for a week, with the Japan Meteorological Agency warning that a magnitude 8 or higher earthquake could strike over the next few days.

The northeastern region of Japan was hit by a magnitude 9.1 earthquake in 2011, the deadliest in its history, just two days after it experienced an earthquake in the magnitude 7 range.

The government, therefore, issues a mega-quake warning whenever the region is hit by a significant earthquake, according to Reuters.

However, earthquakes are notoriously unpredictable.

2025-12-09T12:22:36.757ZJapan earthquake update

Patrick PesterTrending News Writer

2025-12-08T23:40:09.924Z

Patrick PesterTrending News Writer

2025-12-08T23:40:09.924Z

See you later

2025-12-08T22:47:42.407ZOld oil learns a new trick

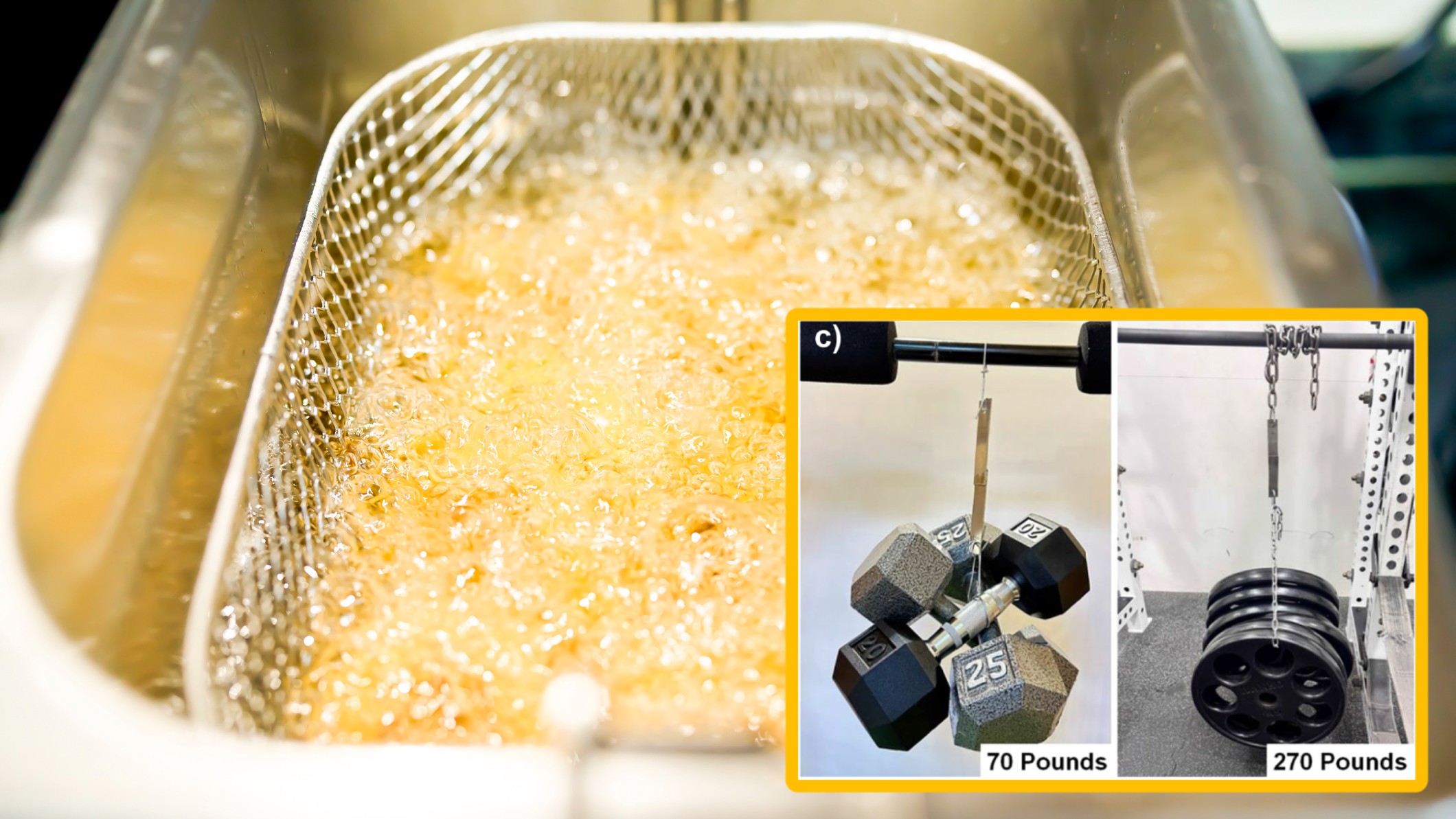

What should you do with the leftover cooking oil in your pot after dinner? Pour it down the drain and feed the growing fatberg under your town? Or maybe do what a team of chemists just did, and use it to make a super-sticky adhesive polymer with unbelievable strength.

As described in a recent study in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, the researchers devised a way to break down waste oil molecules, then recombine them in a variety of ways. One recombination resulted in a super-adhesive polyester plastic.

When the team used this polyester to glue two metal plates together, they found it could hold up hundreds of pounds of weight, and even tow a car. Read all about the amazing discovery in contributor Mason Wakley's new story on Live Science.

Brandon SpecktorSpace and Physics editor

2025-12-08T21:13:23.936Z

Brandon SpecktorSpace and Physics editor

2025-12-08T21:13:23.936Z

Watch 3 astronauts return from the ISS

Three astronauts — NASA's Jonny Kim and Russian cosmonauts Sergey Ryzhikov and Alexey Zubritsky — will be making the long journey home tonight. The trio has orbited Earth together 3,920 times, traveling a mind-boggling 104 million miles (167 million kilometers) since they launched to the International Space Station (ISS) in April, according to NASA.

The trio is scheduled to leave the ISS via a Soyuz spacecraft today at 8:41 p.m. EST (0141 GMT on Dec. 9) and will land in Kazakhstan near the city of Dzhezkazgan, Live Science's sister site Space.com is reporting.

The journey is scheduled to last around 3.5-hours — a speedy trip when you consider that it takes about 6 hours to fly between New York and San Francisco on a commercial plane.

Space.com is streaming the return trip live, so you can watch the journey there.

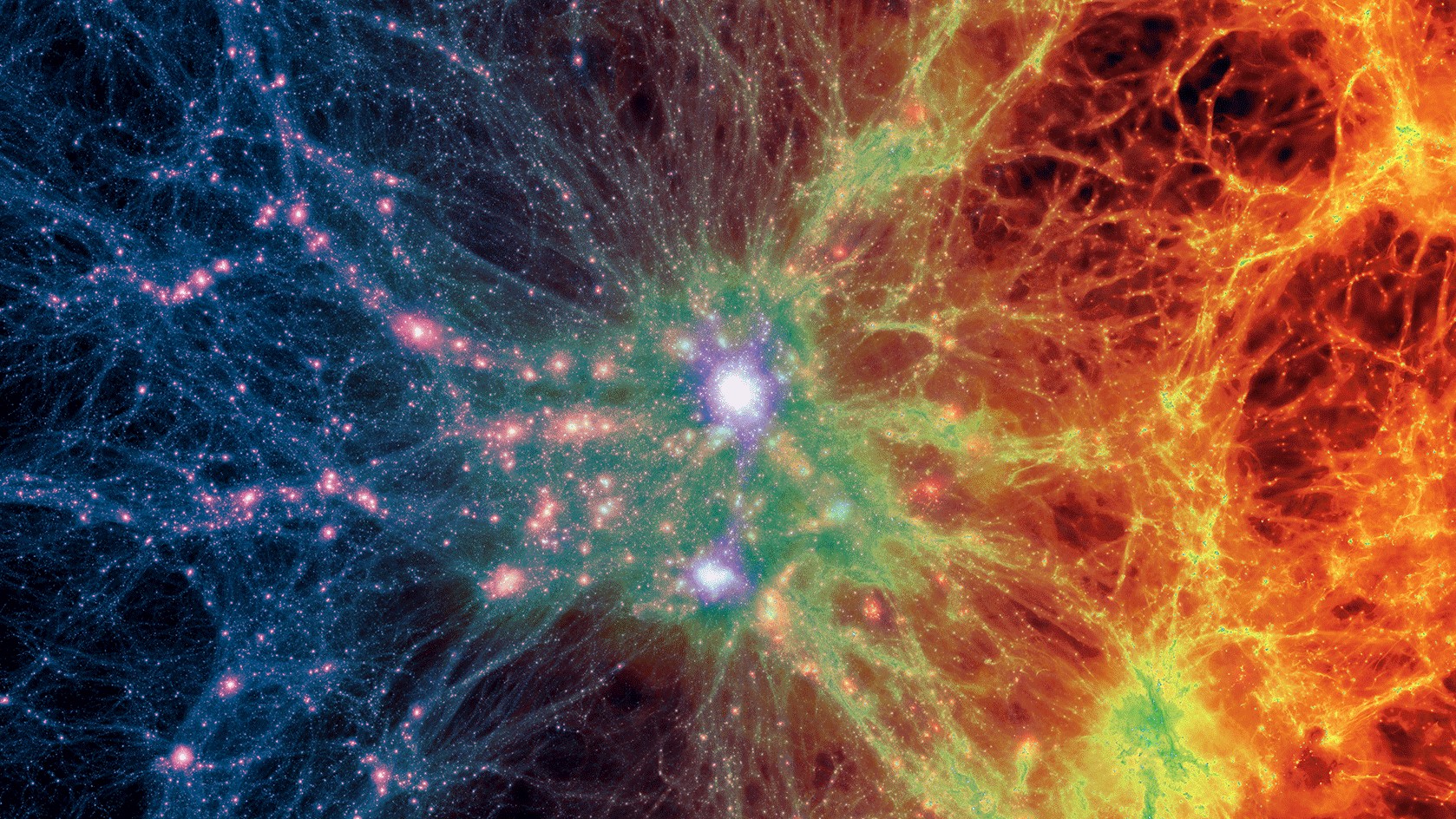

2025-12-08T20:39:09.085ZDark matter hunt fails — and scientists are excited

A Herculean effort to search for dark matter has found no evidence for the elusive substance. That's the takeaway from a gigantic particle detector located a mile underground in South Dakota.

The 417-day-long experiment, known as LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ), looked at the light signatures released as particles collide with xenon atoms in a giant vat, which is placed deep underground so that most particles from space cannot muddy the results.

Dark matter, which emits no light yet exerts gravitational force, is thought to make up most of the universe. And the new findings tightly constrain the properties of one the leading candidates for dark matter.

You can read all about why scientists are actually happy about these negative results in contributor Elizabeth Howell's story here.

Tia GhoseEditor-in-Chief (Premium)

2025-12-08T19:47:05.712Z

Tia GhoseEditor-in-Chief (Premium)

2025-12-08T19:47:05.712Z

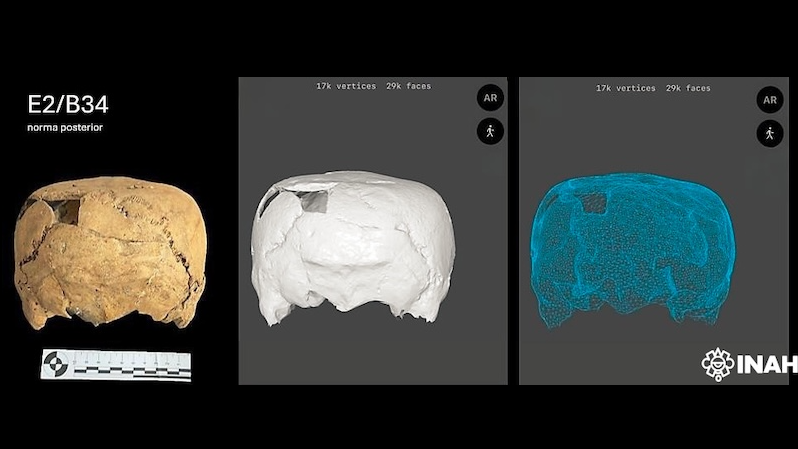

You blockhead!

In Charles Schultz's Peanuts comic strip, Lucy often calls Charlie Brown a "blockhead." Archaeologists in Mexico recently discovered another kind of blockhead — a man whose skull had been shaped as an infant into something resembling a cube.

While head-shaping (also called cranial vault modification) is a practice that people around the world and through time have done to their kids, this particular shape was a surprise to researchers, who'd never seen it in that area of Mexico before.

For more information on the skull and the man it belonged to over a millennium ago, check out my coverage here.

Kristina KillgroveStaff writer

2025-12-08T19:23:47.083Z

Kristina KillgroveStaff writer

2025-12-08T19:23:47.083Z

U.K. sign off

2025-12-08T19:21:25.860ZEarthquake injuries and damage

There have been some reports of injuries and damage in Japan as a result of the magnitude 7.6 earthquake that struck off Japan's main island earlier today. However, these initial reports are limited.

Sky News reported that several people have been injured in coastal communities, but that it was unclear how many.

A hotel employee in Hachinohe City told the Japan Broadcasting Corporation, NHK, of multiple injuries. In this case, everyone involved was conscious.

Japan's Prime Minister, Sanae Takaichi, told reporters on Tuesday morning local time that seven injuries had been reported, according to Reuters. The government has set up a task force in response to the earthquake.

Nuclear power plants appear to be working normally, according to NHK.

This is a developing story and we expect more details to emerge over the next 24 hours.

2025-12-08T18:23:01.140ZTsunami hits Japan

A tsunami has hit Japan following a magnitude 7.6 earthquake off the northeastern coast of Honshu, the country's main island, earlier today.

The Japan Meteorological Agency has recorded tsunami waves hitting Japan's eastern coastline. The precise height of the waves is unclear at this time, but most are in the 3-foot-tall (1 meter) or less category.

There are no reported deaths at this time, although there are some reports of injuries.

Japan downgrades tsunami warning

Japan has downgraded its tsunami warning to a tsunami advisory. The initial warning meant that the authorities expected a maximum tsunami height of between 3.3 feet and 9.8 feet (1 and 3 m).

However, an "advisory" level means that the expected maximum height has been reduced to 3.3 feet, in keeping with the wave heights recorded thus far.

2025-12-08T17:12:47.618ZLook out for Northern Lights

NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center has issued a strong G3 geomagnetic storm watch for tomorrow (Dec. 9), with the potential for visible auroras over many U.S. states from the lower Midwest to Oregon.

The aurora forecast comes as multiple blasts of plasma, or coronal mass ejections (CMEs), hurtle toward Earth from the sun. CMEs have the potential to clash with Earth's magnetic field and trigger geomagnetic storms.

Tomorrow's strong geomagnetic storm forecast is associated with the eruption of a solar flare on Saturday. The resulting CME is predicted to arrive at midday tomorrow.

The Space Weather Prediction Center noted that the CME could also have limited, minor effects on technological infrastructure, but this can usually be mitigated.

And tonight…

Parts of the Northern Hemisphere could see some auroras on Monday, according to Live Science's sister site Space.com.

The Space Weather Prediction Center has forecast a less intense G1 geomagnetic storm as a result of a separate CME that left the sun on Dec. 4, while the U.K.'s Met Office has the more intense G3 watch in place for tonight and tomorrow.

Our sun is very active at the moment. The Space Weather Prediction Center recorded another powerful solar flare earlier today. The X1.1-level flare triggered high-frequency radio disruptions over parts of Australia and southern Asia, according to NOAA.

Patrick PesterTrending News Writer

2025-12-08T15:51:12.794Z

Patrick PesterTrending News Writer

2025-12-08T15:51:12.794Z

Rare sacrificial complex found in Russia

Russian archaeologists recently discovered a collection of hundreds of horse bridle bits and bronze beads near the burial mounds of high-status nomads from the fourth century B.C.

While the artifacts themselves are not exactly surprising — after all, these nomadic peoples relied on horses for travel — their collection as a kind of "sacrifice" is unusual.

To learn more about this discovery, which oddly included a gold plaque depicting a tiger, check out my coverage here.

Kristina KillgroveStaff writer

2025-12-08T15:38:58.300Z

Kristina KillgroveStaff writer

2025-12-08T15:38:58.300Z

Japan hit by major earthquake

A magnitude 7.6 earthquake has hit off the northeastern coast of Japan's main island, Honshu. The earthquake struck at 11:15 p.m. local time (9:15 a.m. EST).

The Japan Meteorological Agency has issued tsunami warnings in three regions: the central part of the Pacific Coast of Hokkaido region, the Pacific Coast of Aomori Prefecture and Iwate Prefecture. The expected maximum tsunami height is between 3.2 and 9.8 feet (1 and 3 meters).

The earthquake was most intense in Hachinohe City where there was a seismic intensity of 6+ — such intensity means it is "impossible to remain standing or to move without crawling," according to the Japan Meteorological Agency's explanation of seismic intensity.

Tsunami Info Stmt: M7.6 Hokkaido, Japan Region 0615PST Dec 8: Tsunami NOT expected; CA,OR,WA,BC,and AKDecember 8, 2025

The U.S. National Tsunami Warning Center tweeted at 9:32 a.m. EST that a tsunami was not expected in California, Oregon, Washington, British Columbia or Alaska.

Sophie BerdugoStaff writer

2025-12-08T14:35:58.193Z

Sophie BerdugoStaff writer

2025-12-08T14:35:58.193Z

Live Science news roundup

- Lost Indigenous settlements described by Jamestown colonist John Smith finally found

- Strangely bleached rocks on Mars hint that the Red Planet was once a tropical oasis

- 1,800-year-old 'piggy banks' full of Roman-era coins unearthed in French village

- New NASA, ESA images show 3I/ATLAS getting active ahead of its close encounter with Earth

'Hobbit' extinction

A drought may have doomed the small ancient human species Homo floresiensis, nicknamed "the hobbit," Live Science contributor Owen Jarus reports.

New research suggests that declining rainfall could have reduced the population of Stegodon (extinct elephant relatives) that H. floresiensis relied on for food, and, in turn, forced the Hobbit to compete with modern humans (us).

H. floresiensis lived in Indonesia from at least 100,000 years ago until about 50,000 years ago. Researchers still have a lot to learn about these enigmatic ancient humans, the remains of which have only ever been found in one cave, and it remains uncertain whether they interacted with us.

Species typically go extinct for multiple reasons. In the case of H. floresiensis, a volcanic eruption may have also been a significant factor in their demise.

Read the full story here.

2025-12-08T13:00:33.681ZCamera lost in lava fountain

Good morning, science fans! Patrick here to launch another week of our science news blog coverage.

Hawaii's Kilauea volcano erupted with spectacular, giant lava fountains over the weekend and consumed a U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) camera.

The remotely operated camera filmed its own demise inside the Halema'uma'u crater on Saturday (Dec. 6) as a wall of volcanic debris approached and knocked it offline.

Kilauea volcano is one of the world's most active volcanoes and has erupted almost continuously on Hawaii's Big Island for more than 30 years.

The latest activity marked the 38th episode of the Kilauea summit's eruption cycle, which began on Dec. 23, 2024. We've seen plenty of lava fountains before, but the USGS's cameras are rarely this close to the action.

Patrick PesterTrending News Writer

LATEST ARTICLES

Patrick PesterTrending News Writer

LATEST ARTICLES 1Stunningly preserved Roman-era mosaic in UK depicts Trojan War stories — but not the ones told by Homer

1Stunningly preserved Roman-era mosaic in UK depicts Trojan War stories — but not the ones told by Homer- 2Mysterious X-ray signal from deep space may be the scream of a star ripped apart by two black holes

- 3Amazon rainforest is transitioning to a 'hypertropical' climate — and trees won't survive that for long

- 4Scientists create new solid-state sodium-ion battery — they say it'll make EVs cheaper and safer

- 5'It is the most exciting discovery in my 40-year career': Archaeologists uncover evidence that Neanderthals made fire 400,000 years ago in England